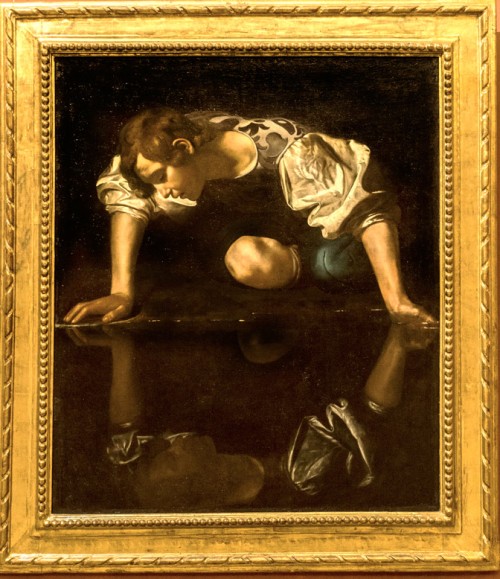

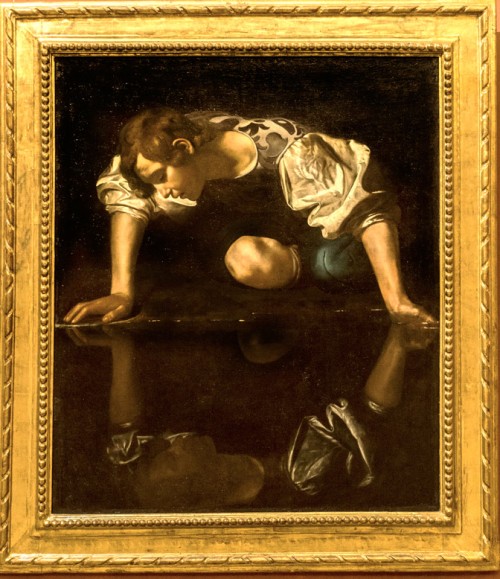

Caravaggio’s Narcissus at the Source – a tragedy of unfulfilled love, or perhaps a story about the essence of art

Narcissus at the Source, Caravaggio?, fragment, Galleria dell’Arte Antica, Palazzo Barberini

Narcissus at the Source, Caravaggio?, Galleria dell’Arte Antica, Palazzo Barberini

Narcissus at the Source, Caravaggio?, Galleria dell’Arte Antica, Palazzo Barberini

Narcissus at the Source, Caravaggio?, fragment (reflection in the water), Galleria dell’Arte Antica, Palazzo Barberini

Narcissus at the Source, Caravaggio?, fragment, Galleria dell’Arte Antica, Palazzo Barberini

Narcissus at the Source, Caravaggio?, fragment, Galleria dell’Arte Antica, Palazzo Barberini

In a dense, dark forest a handsome youth by the name of Narcissus – “who combined both feminine and masculine graces: more than one beauty desired his embraces. Yet oblivious was he to the love, deaf to their sighs" – kneels near a stream to quench his thirst and at that moment he notices his reflection. Taken back by its beauty he feels unbridled, yet impossible to fulfill love. The whole world means nothing to him, he stops eating and drinking and in vain leans towards the surface of the water, with hopes of coming closer. Weakened, and utterly miserable he dies from love, and in the place of his death, a flower emerges out of the ground – a narcissus.

In a dense, dark forest a handsome youth by the name of Narcissus – “who combined both feminine and masculine graces: more than one beauty desired his embraces. Yet oblivious was he to the love, deaf to their sighs" – kneels near a stream to quench his thirst and at that moment he notices his reflection. Taken back by its beauty he feels unbridled, yet impossible to fulfill love. The whole world means nothing to him, he stops eating and drinking and in vain leans towards the surface of the water, with hopes of coming closer. Weakened, and utterly miserable he dies from love, and in the place of his death, a flower emerges out of the ground – a narcissus.

That is how in a myth about Narcissus (Metamorphoses III) Ovid tells us the story of a boy whose future is uncertain. “The seer (Tiresias) asked whether, Narcissus would live a long life, to a ripe old age, replied, if he does not discover himself”. The youth rejected the love of the nymph Echo, who with a broken heart retreated to a cave and the only thing that was left behind was a voice repeating the words of others. This angered the goddess of just retribution and fate, Nemesis, who as punishment sent Narcissus to a source, in which he saw his reflection. In accordance with the prophecy of Tiresias, in order to survive the boy had to reject love of himself and the delight at seeing his own image and needed to learn to love others.

In the painting, we can see him shortly before his death, infatuated with himself, hypnotized by the illusion, and in love with an image without a body. In psychology his figure is connected with the phenomenon of narcissism – a character trait focused on the desire to appeal to others and arouse admiration. As a result, Narcissus has become a symbol of egoism and egotism, a person, who does not show empathy towards others and cannot show feelings towards others, does not care about others and expects unconditional devotion.

However, does the Narcissus shown in the painting freeze in admiration of himself, or does he perhaps see a reflection of someone completely unknown to him and falls in love with a stranger? Perhaps our hero is a self-conscious, extremely sensitive youth, who avoids contact with others due to an all-consuming doubt and low self-esteem. He flees from "normal" love out of fear of responsibility, criticism, and shame. The punishment of the divine Nemesis is not for unreturned love but rather for the poignant feeling of emptiness, where there is no room for love. The love which Narcissus seeks is only an illusion, and he becomes its prisoner.

The composition of the work is cramped, it is closed off in a circle, while the figure of the main hero occupies almost the entire canvas, building a truly claustrophobic space. The painting is bereft of any context, dark, almost monochromatic, with a dominance of bronzes, intersected with dirty white, lead-silver, and celadon. In it, we do not notice the silhouettes of the trees and forest described in the myth, while the water of the stream seems to be no more than a dirty puddle. The reflection is fuzzy, slightly foggy. The figure of Narcissus emerges out of this gloom, thanks to a sharp light placed on the left, which exposes the body and clothing of the youth.

The topic of Narcissus at the source was a subject that was often undertaken by artists of the early Baroque, Giovanni Battista Marino, a well-known poet of the time, devoted one of his poems to him. However, is the person in front of us a mythological figure, or did the creator of the painting used the book La Pittura (1435), in which, its author, an architect, and a theoretician of art of the Renaissance, Leon Battista Alberti names Narcissus as the inventor of painting? Does not (art) painting strive to encompass every element of our life? – asks Alberti. Therefore, the topic of the work would not be a story of egoistical love, but the art that Narcissus discovers. Fascinated with the illusionist image of the world reflected in the water, he desires to capture it, keep it forever, and immortalize it. The goal of art is beauty, while the method of creating said beauty is the imitation of nature, as Alberti would have said. Every person who enters the world of art forgets the real world. He may immerse himself in the created one, and be seduced by the artistic vision. This is what art is – an illusion, a detachment from real life.

This exceptionally poetic image is attributed to Caravaggio (Michelangelo Merisi). The first person to do this was Roberto Longhi, the one who truly discovered this artist after years of languishing in obscurity, as he saw the painting in 1913 in the home of his acquaintance. He believed that the painter completed it during his stay at the court of Cardinal Francesco Maria del Monte (1597-1599). Currently, the composition is found in one of the rooms of the Palazzo Barberini, and on a plaque, with the author's name, there is a question mark. Why we may ask. Most historians attribute the painting to the great Lombard, however a few claim that he was not the author. The painting was connected with various artists who gathered around Caravaggio, among others his friend Orazio Gentileschi, whose Madrid version of David with the Head of Goliath boasts a similar figure. Ultimately it was attributed to Giovanni Antonio Galli, known as Lo Spadarino. The attribution of the painting remains uncertain since we (still) do not have documents, contracts, or information about, whom it belonged to and who commissioned it. The only clue leads to a certificate issued in Rome in 1645, where a painting entitled Caravaggio's Narcissus, was allowed to be taken out of the city into Savona. However, whether it was this very painting or whether it was correctly attributed – we do not know.

The story of the painting shows how complicated the work of researchers dealing with the attribution of paintings of old masters really is, as they spend years researching their lives. They undertake numerous studies and collect bulletproof evidence in order to document the provenance of a painting. In attributing it to Caravaggio, Longhi was driven by intuition, but that is not enough, to be certain. Especially, since the creation of copies and forgeries was a very common procedure at that time while spying on one's fellow artists and dialogue with their works – something obvious. Certain details point to Caravaggio, such as the puffed sleeves and the embroidery on Narcissus's vest, similar to the one found in the painting Penitent Magdalene (Galleria Doria Pamphilj). Yet similar patterns were painted by other artists of that time as well, including Galli. Another proof would perhaps be the method in which the painting support was developed. A radiographic test showed typical for Caravaggio lines made with the tip of the paintbrush, which are a type of sketch on wet paint to draw over the composition of the painting.

Did Lo Spadarino – a little-known painter, but a very talented one – paint a copy of an unknown painting of Caravaggio, or did he imitate his style, or perhaps he created a fully original work (and he was able to do it)? That is the question. The only thing that remains is hope, that one day we will find the response in the archives, but regardless of what it may be Narcissus at the Source is one of the most beautiful paintings of the time period.

Narcissus at the Source, Caravaggio?, 1597–1599, oil on canvas, 113 x 95 cm, Galleria dell’Arte Antica, Palazzo Barberini

If you liked this article, you can help us continue to work by supporting the roma-nonpertutti portal concrete — by sharing newsletters and donating even small amounts. They will help us in our further work.

You can make one-time deposits to your account:

Barbara Kokoska

BIGBPLPW 62 1160 2202 0000 0002 3744 2108

or support on a regular basis with Patonite.pl (lower left corner)

Know that we appreciate it very much and thank You !